-

(单词翻译:双击或拖选)

Hong Kong

05 February 2007

Many leaders in Asia see a European model of integration1 as the way forward for Southeast Asia. But while the Association of Southeast Asian Nations has taken steps toward greater regional economic integration, experts doubt whether the organization will be able to follow the European Union's example any time soon. Claudia Blume reports from VOA's Asia News Center in Hong Kong.

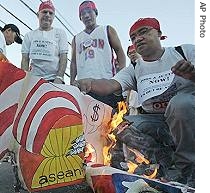

Protesters burn a mock ASEAN logo and a US flag during their "jogging for jobs and justice" protest,Cebu, Philippines (File)

Forty years after the founding of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, there is a growing acknowledgment that the organization needs to reinvent itself to remain relevant. Many believe that the way to go for ASEAN is to push for European Union-like integration.

Benito Lim is a political scientist at Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines. He says ASEAN's goal is to become a unified2 market similar to the E.U.

"That is the eventual3 aspiration4 of all member nations, that once we are integrated we will be able to act as a bloc5, especially for negotiating with other countries on the selling of our products, on tariffs6 and all other issues pertaining7 to economic and trade relations," said Lim.

At last month's ASEAN summit in the Philippine city of Cebu, the organization moved a step closer toward regional integration. Leaders of the 10 member countries agreed to create a free-trade zone by 2015. They approved a blueprint8 for the group's first charter, which would make ASEAN a more legally defined organization and allow it to impose sanctions on members who do not follow its rules. Currently, ASEAN resolutions are not binding9 on the members.

But there are many stumbling blocks that make it difficult for ASEAN to integrate as fully10 as the E.U.

Masahiro Kawai is dean of the Asian Development Bank Institute in Tokyo. He says the disparities among ASEAN member countries are enormous - unlike the European Union.

"The development gaps among countries are huge - Singapore versus11 Laos or Cambodia," he said. "The income disparities are huge, institutional differences are big, of course political regimes are different across countries, whereas in the case of Europe even 50 years ago there was a lot of homogeneity among core countries in Europe."

While the average per capita gross domestic product in Singapore, one of the richest countries in the world, was more than $26,000 last year, the per capita GDP in Burma, the poorest ASEAN member, was less than $200. Laos and Cambodia are not far above Burma.

Malcolm Cook, program director of the Lowy Institute, a Sydney international policy institute, says another major problem in Southeast Asia that makes integration difficult is that the region's economies compete against each other. Most have similar exports, such as textiles and natural resources, which are exported to similar markets.

"Almost all the economies of Southeast Asia minus Singapore are competing economies," said Cook. "They are not particularly complimentary12, which is different than Europe, especially when Spain, Greece and Portugal joined. So the economies don't trade much amongst each other and compete against each other on world markets - that makes integration both less beneficial and more difficult to achieve."

Lack of economic freedom is another weakness of several ASEAN member countries. This year's "Index of Economic Freedom" - released by the U.S. policy research center the Heritage Foundation in January - ranked Cambodia, the Philippines, Indonesia and Vietnam as "mostly unfree" economies.

Vietnam, for example, was only placed 138 on an index of 157 countries surveyed for their level of economic freedom because of the government's tight controls of most assets and the financial sector13. Laos and Burma's economies ranked as "repressed".

Development in the region is hampered14 by widespread corruption16, which scares away investors17 and can restrict economic growth. According to a 2006 Index released by the corruption watchdog Transparency International, six of the 10 ASEAN countries were among the 50 most corrupt15 countries in the world: Laos, Vietnam, the Philippines, Cambodia, Indonesia and Burma.

Political integration in the region is made difficult by the large differences among government systems, ranging from multi-party democracies such as Indonesia to communist regimes in Vietnam and Laos. Benito Lim says because of this, the proposed introduction of majority voting, replacing ASEAN's customary decision-making by consensus18, is a thorny19 issue.

"It is controversial because one of the principles they are committed to would be commitment to democracy, human rights - and you know most of the ASEAN states are not real democracies so that would be a big problem," added Lim.

Traditionally, ASEAN members have stuck to the principle of not intervening in their neighbors' affairs. The organization has been accused of not taking a strong enough stance against human rights abuses, particularly by Burma.

Masahiro Kawai says, however, that the grouping has started to become more vocal20.

"They had [an] implicit21 agreement not to interfere22 with each others' domestic affairs. But in order to make further progress for integration of course you have to talk about countries' businesses economic issues, and to some extent political issues," said Kawai. "So things are moving in the right direction."

Kawai thinks that to strengthen integration, considerable economic, institutional and political convergence has to take place, and that will take time.

Kawai and other experts say that the introduction of a single Asian currency, similar to the euro, is even further away on the horizon.

Talk about an Asian currency unit, aimed at bolstering23 monetary24 stability, spurring economic growth and evening out disparities, has gone on for years. It particularly gained momentum25 during the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990's. But ASEAN has pushed the topic off the table for now. Malcolm Cook says the organization is focusing first on less ambitious goals such as Asian bond markets and on encouraging countries in the region to borrow regional currencies instead of relying on dollar loans.

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

integration

|

|

| n.一体化,联合,结合 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

unified

|

|

| (unify 的过去式和过去分词); 统一的; 统一标准的; 一元化的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

eventual

|

|

| adj.最后的,结局的,最终的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

aspiration

|

|

| n.志向,志趣抱负;渴望;(语)送气音;吸出 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

bloc

|

|

| n.集团;联盟 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

tariffs

|

|

| 关税制度; 关税( tariff的名词复数 ); 关税表; (旅馆或饭店等的)收费表; 量刑标准 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

pertaining

|

|

| 与…有关系的,附属…的,为…固有的(to) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

blueprint

|

|

| n.蓝图,设计图,计划;vt.制成蓝图,计划 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

binding

|

|

| 有约束力的,有效的,应遵守的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

fully

|

|

| adv.完全地,全部地,彻底地;充分地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

versus

|

|

| prep.以…为对手,对;与…相比之下 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

complimentary

|

|

| adj.赠送的,免费的,赞美的,恭维的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

sector

|

|

| n.部门,部分;防御地段,防区;扇形 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

hampered

|

|

| 妨碍,束缚,限制( hamper的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

corrupt

|

|

| v.贿赂,收买;adj.腐败的,贪污的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

corruption

|

|

| n.腐败,堕落,贪污 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

investors

|

|

| n.投资者,出资者( investor的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

consensus

|

|

| n.(意见等的)一致,一致同意,共识 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

thorny

|

|

| adj.多刺的,棘手的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

vocal

|

|

| adj.直言不讳的;嗓音的;n.[pl.]声乐节目 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

implicit

|

|

| a.暗示的,含蓄的,不明晰的,绝对的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

interfere

|

|

| v.(in)干涉,干预;(with)妨碍,打扰 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

bolstering

|

|

| v.支持( bolster的现在分词 );支撑;给予必要的支持;援助 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

monetary

|

|

| adj.货币的,钱的;通货的;金融的;财政的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

momentum

|

|

| n.动力,冲力,势头;动量 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|