VOA标准英语10月-Afghanistan Relatively Unscathed by World Financi(在线收听)

|

| Merchants on the bank of the dried-up Kabul River |

In Kabul, there are no panicky shouts from floor traders. There is no stock exchange, nor any organized commodities market. The ideal place to measure the economic pulse of one of the world's poorest countries is on the banks of the dried-up Kabul River.

Here vendors hawk fruit, carpets, socks and just about everything else the majority of Afghans require for daily life. Their shouts compete with the pleas of beggars also trying to draw the attention of passersby.

An unemployed young man on a family errand, Shafiq Ullah, freshly returned from an extended stay in Iran, walks past the merchants sitting in the dirt and pops into a fabric shop. The global credit crunch, bank liquidity and gyrating stock prices on the world's bourses are the farthest thing from his mind.

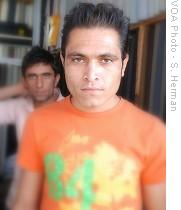

|

| Shafiq Ullah in a Kabul fabric shop |

Ullah says what is affecting the economy of this country is the insurgency, endemic unemployment and official corruption, not what is happening on Wall Street.

About 100 meters downriver, at the Sarai Shahzada money exchange market, the national currency, the Afghani, is holding steady at about 50 to the dollar.

Veteran currency dealer Haji Abdul Wali Ahmadzai agrees that, so far, the global financial crisis is not causing trouble for Afghanistan's economy. But he is hearing predictions that it will soon have an impact.

|

| Currency dealer Abdul Wali Ahmadzai counts money as one of his colleagues looks on at the Kabul money market |

Ahmadzai adds that, as a money changer, what he has noticed is that the Pakistani rupee has quickly depreciated 30 percent against the U.S. dollar. He says that is making life difficult for the many Afghans on the Pakistani side of the border or those doing business there.

For many higher up the socio-economic ladder, the past seven years have been a boon after the decidedly anti-capitalistic Taliban were chased out of power.

Since then, Afghanistan has been enjoying double-digit percentage growth. The economy has doubled in size in the past five years with construction projects dotting major cities, although illicit opium remains the top export.

The president of the state-owned Pashtany Bank, Hayat Dayani, says despite all of the domestic turmoil, Afghans remain bullish.

"We hope this will continue for another five to 10 years, at least," Dayani said. "The way the things look like, still with this much of insecurity and, also, the blasts which are happening in Afghanistan, still the Afghans are those who are investing."

|

| Vendor selling Koranic wall hanging at outdoor Kabul market |

Afghanistan's 16 commercial banks have total assets of only about $1.5 billion. That is woefully inadequate to meet the tremendous demand for credit.

Dayani at Pashtany Bank vows that with whatever money domestic banks have, they are not going to make the same mistakes committed by American bankers who made loans to unworthy borrowers.

"We will not give to anyone credit that easy the way it was in America," Dayani noted. "Suppose someone wants 100,000 [dollars] U.S. We have to get from him at least 200,000 as a guarantee, as a collateral. Only then we can provide him credit. So it means that credit, what the bank is providing, is 100 percent safe."

The vast majority of Afghans, being rural and poor, will never see the inside of a bank and are more likely to engage in bartering than borrowing.

|

| A man selling religious trinkets and offering prayers for improvement of health |

Two-thirds of the country's gross domestic product sill comes from foreign aid. But currency dealer Ahmadzai says few of those billions of dollars in aid trickle down to his customers on the bank of central Kabul's dusty and dry river bed.

He notes there is no investment in the dominant agriculture sector. No big factories are being built to employ people. All those dollars, he complains, are in the hands of a few people. He says it is like a hungry man seeing bread advertised on television; he desires the food but it is impossible to reach through the TV screen to get it.

That is a scenario the global economy, no matter which way it goes, is unlikely to change for the average Afghan.